Producing Champagne - How Hard Can It Be?

In a nutshell all that has to be done is:

Grow grapes, harvest grapes, crush grapes, ferment the juice, blend with other juices, add yeast and sugar, bottle it, ferment the mixture, age the blend, riddle the bottles, disgorge the plug, add sugar, cork it, label it, age it, pack it, sell it.

Even a brief glance at this abbreviated list shows that the production of champagne is not a routine assembly activity where you start with a pile of components and end up with a shiny new bauble. Moreover it is more complex and labour and capital intensive than any other form of wine production whether it be the hallowed soils of the Medoc or a dozen vines on my allotment.

I now plan to take the reader through each stage of the process. What the reader should ask themselves is how does this activity differ depending on whether it is a small family owned Grower enterprise or a multibillion dollar corporation. Before you even start the answer is clear, apart from the advantages of the economies of scale enjoyed by the monster corporation, there are no differences. So why the price difference? It’s all in the perceived value of a brand.

Grow grapes

Literature, opinions, diktats and philosophies on growing grapes are legion. Decisions in the Champagne about what, where and in what orientation were all taken centuries ago, so one might assume that experience and accumulated wisdom have arrived at the correct conclusions.

Families have parcels of land of varying sizes which their antecedents acquired normally in the vicinity of their village. Fortunately in part due to the efforts of one Raoul Chandon the only part of the Champagne area to be badly affected by Phyloxera was the Marne. Nevertheless vines have a life span and a continuous programme of pruning, care and maintenance is required to keep them vigorous, productive and concentrating their efforts on fruit production rather than foliage.

On my allotment I took these decisions myself based on a modicum of knowledge gleaned from one or two books. One row of Phoenix (created in 1964 as the result of a cross between Bacchus and Villard Blanc) and one row of Dornfelder (a red grape developed in Germany in 1955). Planted North/South with a hedge to the east to provide shelter.

Pruning and management of the leaf canopy is vital in maintaining the microclimate around the plant to inhibit mould and encourage healthy fruit. Vine roots are immensely penetrative and will burrow down tens of metres to ensure a consistent supply of moisture.

Harvest Grapes

La Vendage. If you visit the Champagne area in August it will seem almost abandoned. Everybody takes a week or two off and goes on holiday in

order to prepare for the work ahead. The date of the harvest varies from year to year, from variety to variety and from village to village. It is a balancing act supported by the twin

pillars of science and experience to decide when the fruit has the optimum balance of sugar and acid and is in the best condition to make the journey from vine to pressoir.

On my allotment La Vendage took place one dry day in early October. There were one or two bunches of fruit that were starting to rot and not knowing whether this rot was of the noble variety I decided that it was time to act. My twelve vines yielded a total of 20 kilos of fruit. Unlike the Vignerons of Champagne my grapes lay in a couple of boxes for a day or two before being pressed.

Crush Grapes

Sounds easy. Grapes are crushed in batches (marcs) which vary by variety and/or area. A batch is normally 4,000 kgs of grapes which is not allowed to yield more than 25.5 Hectolitres. The first pressing is called La Cuvee’ which is collected separately from the second pressing known as ‘La Taille’ The Cuvee is the purest juice and is rich in sugars and acids which endow the wine with subtle perfumes, freshness and provide finness. The taille has less acids but a higher proportion of mineral salts and coloured material. It produces wines whose aromatic characteristics are stronger and fruitier when young but will not age so well. Large manufacturers use rectangular hydraulic presses and small enterprises use old fashioned circular pressoirs.

Ferment Juice

The juice, be it the cuvee or the taille, runs out of the pressoir and undergoes fermentation normally in stainless steel vats but in some cases in oak casks. (Krug and Alfred Gratien) The yeast consumes the natural grape sugars, producing alcohol and carbon dioxide. The process is quick and warm (several weeks at 18-20°C) in order to produce a neutral wine high in acidity. Some producers then allow a malolactic fermentation to proceed to reduce acidity. The standard winemaking practises of filtering and clarifying are conducted. Every batch is tracked by variety, vineyard, pressing.

My grapes went in the fruit press. I collected the juice in 1 gallon demijohns and added some yeast and closed off the container with an air water trap to allow the egress of carbon dioxide but not permit the entry of any oxygen. They hubbled and bubbled for several weeks before calming down. The ‘wine’ was then decanted, filtered and bottled.

Blend fermented juices

Ordinarily the word blending suggests that product quality is maintained despite the inclusion of some cheap bulk filler component. The art of blending in the assembly (assemblage) of Champagne is to create a sense of balance. From the Chef de Cave’s point of view he is required to maintain a house style by means of an adroit selection of this year’s wines which may be just his own or a broad selection of wines from across the Champagne area and the addition of wines from previous years to create the standard non-vintage product that everybody expects. In particularly good years the wines selected will be from the year in question only and the output will be called a Vintage product. The small scale family grower does not have the breadth of choice of component wines to choose from. He only has what he has made either this year or what he has held back from previous years. Holding product in stock for a year or five as every production specialist knows is a poor use of cash. Once the selections are made the wines are blended together in large vats with gently rotating paddles. This is followed by a period of stabilisation when the newly blended wine is chilled to -4C for a week to induce crystallisation of tartaric acid rather than it forming in the finished product. A further step of clarification results in a clear wine.

Bottling and initiating secondary fermentation

Prior to bottling a mixture known as ‘Liquer de tirage’ is added. This is a mixture of still Champagne and sugar made from cane or beet, yeast cultures and bentonile alginate additives. The sugar and yeast will fire up secondary fermentation and the additives encourage the resulting plug of spent yeast to slip down the inside of the bottle towards the neck. (As a matter of interest alginates (extracted from seaweed) are the additive in ice cream that makes it soft.) During bottling a hermetic seal using a polythene cap is made. The evolution of Carbon Dioxide during secondary fermentation increases the pressure in the bottle up to 90 psi (average car tyre is 30 psi.) That is why champagne bottles are so thick and weigh as much as 700 grams. The action whereby the Carbon Dioxide dissolves into the wine is called the ‘Prise de Mousse’ – capturing the sparkle.

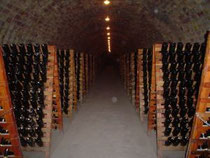

On completion of the secondary fermentation that is to say once the yeast has consumed all the sugars and the sparkle has been captured a period of ageing is undergone. The dead yeast cells (known as lees) by means of autolysis amend the flavour and texture of the wine. The range of flavour characteristics induced include fresh bread, roasted nuts, and salty cheese. Non-vintage Champagnes must age a minimum of 15 months on their lees. The majority will age between 18-24 months. Vintage Champagnes must age a minimum of 3 years on the lees and many wines far exceed this stipulation. Once again having to tie up your working capital for this period of time shows how committed you have to be to produce even the most basic form of Champagne.

The sediment – the lees - which is primarily spent yeast, gathers at the lowest point in the bottle which at this stage is still horizontal. The bottles are stowed in racks known as tirages. The challenge now is to coax the deposits from the side of the bottle to the neck whilst continuing to imbue the wine with flavour from the spent yeast. The traditional method is to twiddle the bottle regularly whilst slowly raising it to a fully inverted position. The charismatic pupitre, a sort of wooden A frame with holes, is the traditional piece of Champenois equipment used. Needless to say in the higher volume environments this has been replaced by a complicated piece of equipment operated hydraulically. In the more artisanal emporia, an old boy clad in the time honoured garb of blue denim dungarees and a blue denim jacket (denim is of course the blue material originally made in Nimes hence de Nimes) spends all day in the cellars giving each bottle a twiddle and gently increasing its inclination to the vertical. This process is known as ‘Remuage’.

Eventually the bottle is fully inverted with all the deposits hard up against the seal. The next challenge is how to remove the debris with the minimum loss of wine and dissolved carbon dioxide. This process is known as disgorging, If this was a pipework repair on a nuclear power plant this would be easy. The pipe would be cryogenically sealed with liquid nitrogen allowing the pipe to be cut open with no loss of radioactive effluent.

Centuries of practise have shown that immersing the neck of the bottle in freezing brine is sufficient to calm the wine down and to allow the sediment to be expelled naturally by the internal pressure once the cap is released. Once again this process can be done at the rate of millions of bottles a day with the aid of high speed machinery or considerably slower by hand when the volumes are lower.

There is still one more action to be undertaken once the seal is off and the spent yeast ejected. Le Dosage. It sounds like something the doctor would recommend if

you had got a nasty little itch in your nether regions but it is in fact the addition of a mixture of pure cane sugar and Champagne. It is called the ‘Liquer d’expedition’ and both makes up the

volume lost during disgorging and determines the final level of sweetness.

|

Brut Nature |

= |

no sugar or under 3 grams/litre of residual sugars |

|

Extra-Brut |

= |

between 0 and 6 g/litre of residual sugars |

|

Brut |

= |

less than 12 g/litre of residual sugars |

|

Extra Sec |

= |

between 12 & 17 g/litre of residual sugars |

|

Sec |

= |

between 17 & 32 g/litre of residual sugars |

|

Demi-Sec |

= |

between 32 & 50 g/litre of residual sugars |

|

Doux |

= |

more than 50 g/litre of residual sugars |

Over the last two centuries, there has been a tendency to drink Champagne with less and less added sugar. In the 19th century, Champagne was drunk very heavily sweetened, with residual sugar levels varying between 50 and 100 g/litre or even more. Today, very little “doux” and “demi-sec” Champagnes are made.

There is some sort of interesting social observation to be made about how when volumes increased and consumption was no longer limited to the toffs and nobility that marketing drove the need for differentiation and refinement. It was no longer a case of the ancient regime simply swilling down a dreadfully sweet and expensive fizzy wine.

With the liquer d’expedition added the bottle is now corked up properly, foil placed around the cork and wire added to prevent a case of premature ejection. French for a cork is a bouchon but it also means a traffic jam. So when you are on your way to Epernay for a visit do not get confused into thinking that the Paris peripherique is littered with Champagne bottles when the radio warns of a bouchon ahead.

Time scale

|

Sep

|

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Jan |

March |

18 – 24 months |

2 weeks

|

|

|

|

Harvest |

First fermentation

|

Blending |

Blending |

Bottling |

2nd fermentation |

Ageing on lees |

Remuage |

Disgorging |

Dosage |